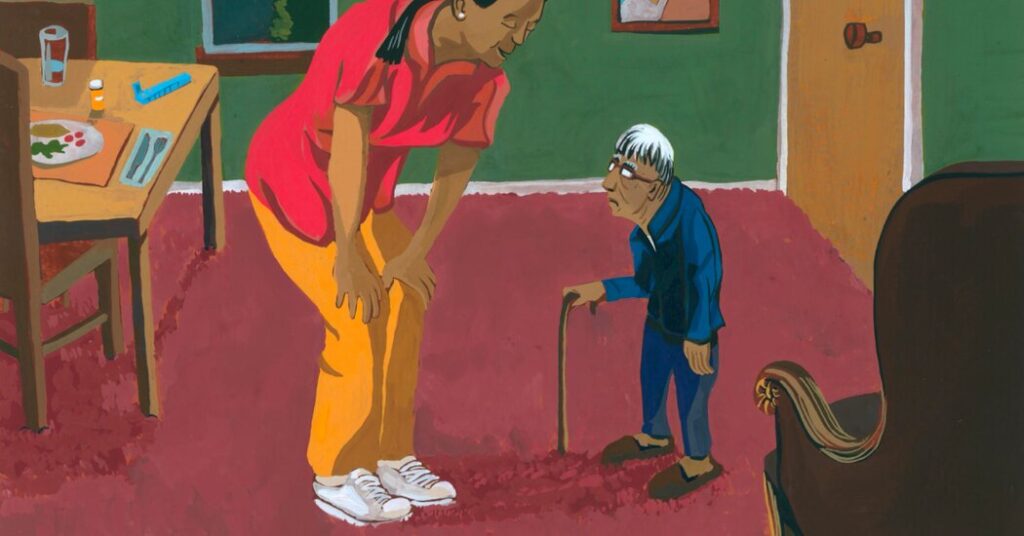

A quintessential instance of elderspeak: Cindy Smith was spending time with her father in his assisted living apartment in Roseville, Calif. An aide attempting to encourage him to do something—Ms. Smith can’t recall the specifics—said, “Let me help you, sweetheart.”

“He shot her a look—under his bushy brows—and replied, ‘What, are we getting married?’” Ms. Smith reminisced, sharing a laugh.

At the time, her father was 92, a retired county planner and a World War II veteran; despite macular degeneration impairing his vision and requiring him to use a walker, he remained mentally sharp.

“He usually wasn’t overly brusque,” Ms. Smith noted. “But he felt he was an adult, and often, he wasn’t treated that way.”

People instinctively grasp the essence of “elderspeak.” “It’s communication with older adults that resembles baby talk,” explained Clarissa Shaw, a dementia care researcher at the University of Iowa College of Nursing and coauthor of a recent article aiming to document its prevalence.

“It stems from ageist beliefs about frailty, incompetence, and dependence.”

Inappropriate terms of endearment are among its features. “Elderspeak can come off as controlling or patronizing, hence the use of words like ‘honey,’ ‘dearie,’ and ‘sweetie,’” said Kristine Williams, a nurse gerontologist at the University of Kansas School of Nursing and another coauthor.

“Negative stereotypes of older adults lead to a shift in our communication style.”

Caregivers may also use plural pronouns: Are we ready to take our bath? This implies the individual lacks autonomy, Dr. Williams noted. “I certainly hope I’m not joining you for that bath.”

Sometimes, elderspeakers will adopt a louder tone, simpler words, or speak in a singsong manner more appropriate for preschoolers, using terms like “potty” or “jammies.”

Using tag questions—It’s time for you to eat lunch now, right?—means you’re asking a question but not providing room for genuine responses, Dr. Williams explained. “You’re essentially instructing them on how to reply.”

Research in nursing homes illustrates the ubiquity of such speech. When Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw, and their team examined video recordings of 80 staff-resident interactions with individuals suffering from dementia, they found that 84 percent featured some form of elderspeak.

“Most instances of elderspeak come from a place of care. People are trying to express their concern,” Dr. Williams stated. “They don’t perceive the negative connotations that accompany such speech.”

For instance, research has indicated a correlation between exposure to elderspeak and behaviors known collectively as resistance to care among nursing home residents with dementia.

“Individuals might turn away, cry, or refuse,” Dr. Williams remarked. “They may close their mouths tightly when being fed.” Occasionally, they may push caregivers away or even hit them.

In response, she and her team created a training program known as CHAT (Changing Talk), comprising three hour-long sessions that include videos of staff-patient communication geared towards reducing instances of elderspeak.

The program was a success. Prior to the training, in 13 Kansas and Missouri nursing homes, nearly 35 percent of interaction time was characterized by elderspeak; this dropped to about 20 percent post-training.

Simultaneously, resistant behaviors accounted for approximately 36 percent of encounter time; afterward, this figure decreased to around 20 percent.

A study performed in a Midwestern hospital with dementia patients also revealed similar declines in resistant behaviors.

Moreover, implementing CHAT training in nursing homes corresponded with a reduction in antipsychotic medication usage. Although the results didn’t reach statistical significance due to a small sample size, the research team considered them “clinically significant.”

“Many of these medications come with a black box warning from the F.D.A.,” Dr. Williams noted regarding the drugs. “They pose risks for frail, older adults due to their side effects.”

Currently, Dr. Williams, Dr. Shaw, and their colleagues have modified the CHAT training for online accessibility, examining its impacts across about 200 nursing homes nationwide.

Even in the absence of formal training, individuals and organizations can take steps to mitigate elderspeak. Kathleen Carmody, owner of Senior Matters Home Care and Consulting in Columbus, Ohio, advises her aides to address clients as Mr., Mrs., or Ms., “unless or until they ask, ‘Please call me Betty.’”

In long-term care, however, families and residents might fear that confronting staff about their language could lead to tensions.

A few years back, Carol Fahy was distressed by how aides at an assisted living facility in suburban Cleveland interacted with her mother, who was blind and had grown increasingly dependent in her 80s.

Referring to her as “sweetie” and “honey babe,” the staff “would crowd around, cooing, and styled her hair in two pigtails atop her head, akin to how one would with a toddler,” described Ms. Fahy, 72, a psychologist from Kaneohe, Hawaii.

Though she acknowledged the aides’ well-meaning intentions, “it felt disingenuous,” she reflected. “It doesn’t create a positive effect. It’s genuinely alienating.”

Ms. Fahy contemplated discussing her concerns with the aides, but “I feared retaliation.” Ultimately, for various reasons, she transitioned her mother to a different facility.

However, addressing elderspeak doesn’t need to be confrontational, according to Dr. Shaw. Residents and patients—or anyone who encounters elderspeak, which extends beyond healthcare settings—can kindly express their communication preferences.

Cultural aspects also come into play. Felipe Agudelo, a health communications professor at Boston University, noted that in some contexts, diminutives or terms of endearment “aren’t indicative of underestimating one’s intellect; they can convey affection.”

Having emigrated from Colombia, he shared that his 80-year-old mother isn’t bothered when a doctor or healthcare worker says “tómese la pastillita” (take this little pill) or “mueva la manito” (move the little hand).

This is customary, and “she feels she’s interacting with someone who genuinely cares,” Dr. Agudelo explained.

“Engage in negotiation,” he suggested. “It doesn’t need to be confrontational. The patient has the right to say, ‘I don’t appreciate being spoken to in that manner.’”

In response, the worker “should recognize that the recipient may come from a different cultural background,” he continued. They can reply, “This is how I normally communicate, but I can adapt.”

Lisa Greim, 65, a retired writer in Arvada, Colo., recently pushed back against elderspeak when signing up for Medicare drug coverage.

She recounted in an email that a mail-order pharmacy began calling frequently because she hadn’t refilled a prescription as anticipated.

These “gently condescending” callers, seemingly reading from a script, often said, “It’s hard to remember to take our meds, isn’t it?”—as though they were sharing in Ms. Greim’s experience.

Irritated by their assumptions and their subsequent question regarding how often she forgot her medications, Ms. Greim informed them that she had ample supply from earlier, “Thank you, but I’ll reorder when I need more.”

Lastly, “I asked them to stop calling,” she noted. “And they did.”

The New Old Age is produced through a partnership with KFF Health News.