BBC

The Treasury has disclosed the divestiture of its last shares in the NatWest Group, marking the bank’s transition to complete private ownership nearly two decades after it was rescued by taxpayer funds during the 2008 financial crisis.

This signifies a notable conclusion to a pivotal era in the narrative of British banking.

In the early hours of Monday, October 13, 2008 – Chancellor Alistair Darling was winding down for the night, while officials surrounded by takeout were finalizing the details of the largest government intervention in private enterprise since World War Two.

The following day, he revealed the first tranche of a rescue operation, costing the taxpayer more than the entire annual defense budget.

In total, the government invested £45 billion (approximately £73 billion in current terms) to acquire an 84% share in the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), which is now incorporated into the NatWest Group.

Luke MacGregor/PA Wire

At that moment, RBS’s liabilities were larger than the total UK economy. Its failure would have had catastrophic consequences.

The pressing question is: why did it take 17 years for the Treasury to dispose of its final holdings?

Moreover, given the emergence of new risks over the years – notably the threat posed by cyber-attacks from hostile entities – how exposed are UK banks today? Are they still deemed “too big to fail,” as they were frequently labeled in 2008? Should Britain find itself in another financial predicament, would the taxpayer again be called upon for a bailout?

‘The focus was never on preserving the banks’

Rick Haythornthwaite, the current chairman of NatWest Group, expressed gratitude to the BBC, emphasizing that both the bank and its workforce appreciate the intervention from 2008.

“Our principal message to the taxpayer is one of profound thanks,” he states. “They were the ones who saved this bank, safeguarding millions of businesses, homeowners, and savers.”

Much has changed since 2008. Approximately £1.5 trillion in outstanding loans have disappeared, alongside tens of thousands of jobs eliminated, and about £10 billion of taxpayer money has been lost – irretrievable.

The government expenditure may appear as a poor investment; however, as Baroness Shriti Vadera, former senior advisor to the government and chair of Prudential, shared with the BBC, this was not a matter of investing, but of rescuing.

“The nationalization of RBS wasn’t a voluntary investment,” she clarifies. “The crucial factor at that time was to evaluate RBS and other banks’ impacts on the economy and especially their capacity to continue functioning – lending and ensuring cash availability in ATMs.

“The objective was never to save the banks; it was to save the economy from the banks.”

The repercussions of a banking collapse would have been severe. Prime Minister Gordon Brown even suggested deploying soldiers to the streets.

In a publication by former Labour aide Damian McBride, Brown reportedly stated: “If banks close their doors, cash machines are inoperable, and shoppers find their cards unserviceable, chaos would ensue.

“If necessities such as food, fuel, or medicine are unattainable, societal breakdown may follow.”

High-risk mortgages and poor loans

RBS was by no means the sole bank at risk of collapse. A surge of problematic loans originated from turmoil within the US mortgage sector. High-risk loans extended to borrowers with subpar credit ratings were repackaged and sold to financial institutions globally.

By 2007, confusion reigned regarding the locations of these hidden risks on bank balance sheets, leading to a halt in interbank lending, resulting in a standstill of the entire global financial system.

Northern Rock had relied on borrowed funds to underwrite its own risky mortgages and, in 2007, the BBC reported that it sought assistance from the Bank of England, triggering a bank run that ultimately culminated in its nationalization in February 2008.

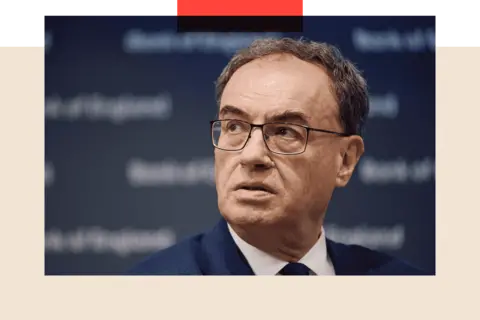

Andrew Bailey, who served as the Chief Cashier during that tumultuous period, believes that failure to nationalize RBS would have resulted in “incalculable” costs.

“The consequences would have been substantial, as it would reflect the collapse of the banking system as we understood it at that time,” Bailey recounts.

Benjamin Cremel/ PA Wire

American banks also faced severe turmoil. In March 2008, Bear Stearns was acquired by rival JPMorgan. By September of the same year, the US mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were nationalized. In the UK, HBOS was taken over by Lloyds, while the collapse of Lehman Brothers defied expectations of a government intervention to rescue it.

For the UK economy, RBS represented the most significant risk. Given the size of its banking sector relative to its economy, RBS was an essential player.

Once a stable establishment, RBS had become, to an extent, the world’s largest bank. It acquired NatWest in 2000 and, just before the crash, acquired Dutch bank ABN Amro.

Its ambitious leader, Fred Goodwin, was knighted for his contributions to banking but eventually became a target of public resentment over the risks taken by banks and the hefty bonuses paid to their executives.

He departed with an annual pension of £700,000, only to be later stripped of his knighthood.

Reuters

In the years that followed the rescue, countless businesses reported that the bankers RBS assigned to assist them were leading them towards failure, driving many to bankruptcy or forcing them to sell their enterprises at bargain prices.

RBS became emblematic of a banking culture characterized by recklessness, arrogance, and cruelty.

So why did it take so long for the government to reduce its holdings in RBS, incurring a £10 billion loss?

Was it a mistake to hold on for so long?

Simultaneously with the acquisition of an interest in RBS, the government also invested in Lloyds, which was sold in May 2017, generating a profit of £900 million.

RBS proved to be considerably more complex than Lloyds, as it operated a vast U.S. division that was undergoing prolonged investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice. The anticipation of substantial fines lingered over the bank for years and was realized when it incurred a $4.9 billion (£3.6 billion) penalty in 2018 related to the U.S. mortgage crisis.

RBS also represented a less appealing investment. It reported a £24 billion loss for 2008 – the largest loss in UK corporate history – and sustained losses annually until 2017.

With the shares suppressed by these apprehensions, the government hesitated to sell its stake at low prices, as this would crystallize a politically sensitive loss for the taxpayer.

Reuters

After all, from 2010 onward, austerity became a priority, and then-Chancellor George Osborne could ill afford to appear as if he were incurring losses through the sale of RBS shares while making cuts elsewhere.

Yet many argue this course of action proved ill-advised, as, akin to a chicken-or-egg scenario, it extended the hesitancy of private investors to acquire shares in a firm predominantly owned by the government.

Baroness Vadera articulated, “I question whether it was necessary to take 17 years to divest from these shares.”

Collapses are ‘less likely – but not impossible’

Mr. Haythornthwaite, who became chairman of NatWest Group in April last year, regards the final sale of shares as a “symbolic” milestone for the bank, its staff, and investors, with broader implications for the nation.

“I hope it heralds a new chapter for our nation,” he remarks. “It enables us to move beyond this phase and genuinely contemplate the future.”

But what exactly does that future hold, and have the lessons of the past truly been learned?

Andrew Bailey certainly believes so, asserting that should a bank encounter difficulties today, it is less likely that taxpayers would be saddled with the burden of a rescue.

Alternative strategies for salvaging a failing bank now exist, including asset acquisitions and emergency funding.

Bailey elaborates, “The key distinction is that we believe we can address bank crises without resorting to public funds. The primary objective is to ensure continuity of services, as they are vital to both the economy and the general public.”

“When we refer to having addressed the issue of ‘too big to fail,’ we mean precisely that we do not require public resources.”

It’s worth noting that the Bank of England now conducts significantly more rigorous stress tests on banks to assess their resilience under adverse conditions such as plummeting property values, skyrocketing unemployment, or soaring inflation.

Sir Philip Augar, a seasoned figure in the City of London and author of numerous banking-related works, concurs that British banks currently find themselves in a more robust position compared to 2008, mainly due to maintaining higher liquid reserves instead of relying predominantly on debt.

“The transformation we’ve witnessed since then involves a substantial reduction in leverage across the board, and the capital requirements for banks have markedly risen. Thus, while it’s less likely that a bank would face collapse today, it remains a possibility.”

Cyber threats are here to stay

Additionally, new threats have emerged.

Consider the series of cyber assaults that have recently compromised the operations of well-known retailers such as Marks and Spencer, Co-op, and Harrods. If a similar attack were to disrupt essential banking functions like corporate lending, payroll, and ATM operations, the repercussions would be profound.

Indeed, Andrew Bailey identifies cyber risk as a rapidly escalating concern in the financial landscape.

“While we must mitigate it, cyber threats will persist as they continue to evolve,” he emphasizes.

“We are contending with malicious actors continuously refining their methods of attack. I must remind institutions that they need ongoing vigilance.”

The recent banking failures in the U.S., such as Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank, underscore another significant risk. Customers no longer have to physically queue to access their funds; this can now be done with a few clicks online.

Banks rely on public trust: clients deposit money with the expectation that they can withdraw it at will. Today’s digital landscape has transformed traditional bank runs into swift online withdrawals.

However, banks do not function like ordinary companies. They are interconnected entities forming the essential network of the economy.

They are the foundational channels through which credit flows, wages are disbursed, and savings are accumulated or withdrawn. When these channels face obstruction, detrimental outcomes invariably follow.

This reality remains as relevant today as it was back in 2008.

BBC InDepth serves as the premier destination for in-depth analysis, featuring fresh insights that question established views and comprehensive reporting on pressing issues. We also present engaging content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer. Your feedback on the InDepth section is always welcome via the button below.